ON a South Australian wetland, scientists have been carefully monitoring the decomposition of 6 tonnes of dead carp.

Other Australian-based researchers have flown to Japan and America to investigate the fallouts from some of the world’s biggest fish kills, while back home, laboratories have been testing a range of animals with a carp-specific herpes virus.

Their findings are all being recorded as part of the $15 million National Carp Control Plan (NCCP), a two-year investigation by world-class scientists, economists, water quality experts, veterinarians and risk assessment specialists trying to determine the impact of a bold initiative designed to reduce the numbers of introduced European carp in our waterways.

The final report should be on the desks of water ministers by the end of the year.

If the plan goes ahead, Australia will be the first country in the world to deliberately release the carp herpes virus, Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), into the environment.

In the meantime, the other 33 nations around the globe whose largely valued carp populations are suffering from the virus are busily trying to eradicate it.

No-one disputes that feral carp are an environmental, economic and social pest in Australia.

They account for up to 90% of the fish biomass in some of the areas of the Murray-Darling Basin, where the slimy toothless monsters suck up mud and gravel from river beds, turning water into a brown, turbid mess.

|

|

| Crowd control: An important food source in many countries across the world, in Australia, introduced carp has proved to be environment and economic disaster, and the race is on to eradicating it from the waterways. |

|

They destroy native fish populations by eating eggs and the vegetation they depend on, increase the frequency of harmful algal blooms, clog up farmers’ irrigation pumps and discourage swimmers, boat users and anglers from enjoying Australia’s precious waterway.

Carp musters and commercial fishing have made barely a dent in their numbers.

The Charlie Carp liquid fish fertiliser factory in Deniliquin, which uses whole European carp in its products, only uses about 400 tonnes of the pest a year.

And although carp are a popular eating fish overseas, it’s difficult to harvest, chill and export them profitably, and there is little local demand as Australians regard carp as a junk fish.

The virus seems to be the only option – but while the plan has support from a range of campaigners, from the National Farmers’ Federation to the Australian Conservation Foundation, almost 4 million people depend on the Murray-Darling for water.

And when some Australians don’t even want health initiatives such as fluoride in their pipes, you can only imagine the fuss about a herpes virus.

Once it’s in the waterway, it’s there to stay. It would only disappear if there were no more carp hosts and since a 70% reduction is the most optimistic expectation, that’s not going to happen.

It’s no wonder NCCP national coordinator Matt Barwick is examining the facts and repercussions from every angle.

Among the most pressing issues is establishing carp densities and populations – essential in calculating virus transmission and logistics for removal and disposal of dead fish.

“If the virus is successful, dealing with the outcome of that success is the basis on which this program will live or die,” says Harold Clapham, managing director of Charlie Carp, who has dealt with more dead carp than most.

If the virus transmission is so successful it proves impossible to extract the subsequent tonnes of carp from inaccessible rivers, there are concerns it could lead to a blackwater event, removing oxygen from the water and killing all other fish in the system.

To prevent this, it’s proposed that the virus will be released in small and controlled areas. To an extent, they’ll be learning as they go.

Says Matt: “There are things dying in the river every day, including fish, but we need to understand if there are thresholds that need to be avoided, if there are variations in different waters, still and shallow versus deep and flowing, and how we achieve appropriate dilution so we don’t compromise water quality.

“However, not all dead carp need to or should be removed. Every carp is a parcel of carbon and nutrients and those are energy sources for the eco system.”

MANAGING CARP

Dr John Conallin, a visiting researcher at the UNESCO-backed IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, is a scientist, fisherman and farmer who lives on the Edward River, a branch of the Murray. He, too, is confident that carp kill is manageable.

Floods or droughts can’t always be predicted, he agrees, and both will affect containment of the virus and disposal of fish kills.

But, he points out, the effects of a fish kill last a few weeks. Carp, meanwhile, have been blighting our water quality for 50 years.

“The risk is very small and short-lived for the long-term benefits and native fish are highly resilient to these types of events.”

Louise Burge, a farmer based near Deniliquin in the Murray region, agrees. She saw massive Murray cod fish kills after blackwater events in 2009 and 2010, but she says that no-clean-up operation was needed.

“They just went through the system.” Numbers also recovered well.

There will be instances when dead carp must be removed, however, and depending on location, a variety of methods are being considered.

These include trawlers that would avoid native fish, booms across waterways, and marine debris barges.

As for disposal, Charlie Carp could triple its capacity without major capital expenditure, and has the experience to roll out plants in other regions.

There have been discussions with Indigenous groups, decentralised land composting for landholders adjacent to waterways has been proposed, and Matt Barwick is excited by research that shows the carcasses could be turned into fishmeal or even energy.

But while the science may look good, there is still the issue of public confidence.

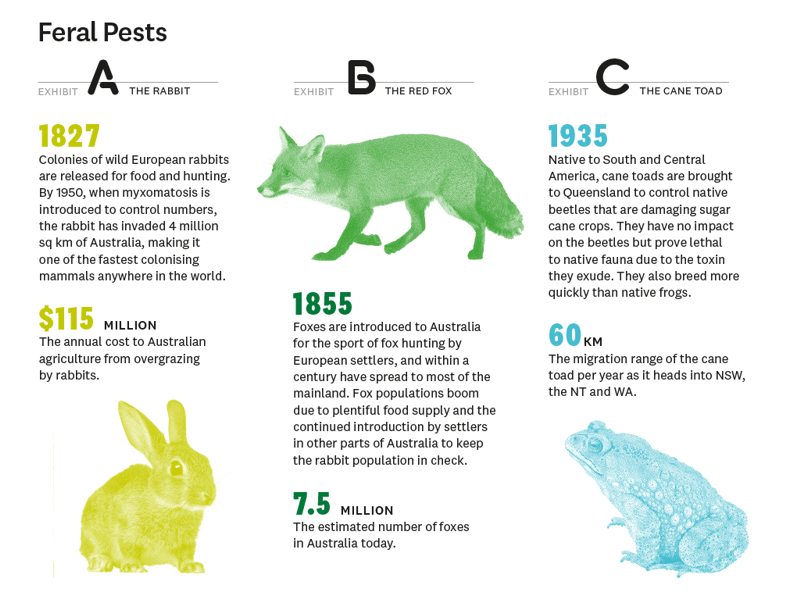

Using bio controls such as the calicivirus to kill rabbits and the cactoblastis moth to kill prickly pear have been outstanding successes, but the cane toad fiasco is the one that remains in popular consciousness.

INTERNATIONAL CRITICISM

|

|

|

Catching carp: Alternatives to a virus release are already being trialled, including this carp separation cage. The specially created trap is designed for use in fishways and captures jumping migrating carp as they pass by. Most native fish do not jump, so they progress safely through. |

NCCP tests have proven the carp virus doesn’t affect other species, including humans.

And although British-based academics Dr Jackie Lighten and Professor Cock van Oosterhout have claimed that, with carp such a popular eating fish overseas, the Australian release of CyHV-3 could affect global food security, Matt points out that hundreds of tonnes of affected carp have already been eaten by humans with no ill effects.

You can bet the loudest protests won’t be made in the regions where carp are a problem, says Harold Clapham.

“They’ll almost certainly come from

environmental inner city lobbies. That’s just a fact of Australian politics – it’s like the water politics, driven by people who’ve never even seen the river.”

Back at her farm, Louise hopes the virus does get the go-ahead. She’s been calling for its use for years and says while it isn’t a silver bullet it will be a very effective population control.

However, with the weariness of one who has seen local wisdom on Murray-Darling management ignored in the past, she wants to see it used as part of an integrated plan, not in isolation.

If the Basin Plan keeps pushing overbank flooding and fails to promote the flowing streams native fish love, it will continue to create perfect breeding pools for carp, she says – and since a 6kg female can produce millions of eggs a year, that could be disastrous.

Dr John Conallin agrees. For the carp virus to have long-term effectiveness, the rivers will simultaneously need to be restocked with native fish that will also reduce carp numbers further by eating them.

As less carp mean more resources for young natives to eat, and therefore even more natives devouring them, balance could be restored.

“I really hope Australia has the balls to do what’s right,” he says, “and the release of the carp virus is the right thing to do. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

|

|

Catching carp: Alternatives to a virus release are already being trialled, including this carp separation cage. The specially created trap is designed for use in fishways and captures jumping migrating carp as they pass by. Most native fish do not jump, so they progress safely through. |