PLANT-BASED milks are soaring in popularity – a trend that is striking an increasingly sour note with the dairy industry. The concern is that consumers are being led to believe that products such as soy, oat, coconut, rice, almond and cashew ‘milks’ are interchangeable with cow’s milk in terms of nutrition.

The dairy industry is now questioning the marketing of these products – an issue that is already being addressed by regulation and labelling elsewhere in the world.

So what's the difference between plant-based milk and dairy milk?

“The way we see it, so-called plant-based milks are trying to use the nutritional quality of milk to sell their products – but in fact there is nowhere near the level of nutrition compared to cow’s milk,” says Colin Thompson, deputy chair of NSW Farmers’

Dairy Committee.

Colin, who runs a Holstein free-stall barn enterprise at Cowra in the NSW Central Tablelands, adds: “We are extremely concerned [plant-based milk producers] are trying to use the word ‘milk’ to convince consumers that their products have the same nutritional quality.”

Colin Thompson on his dairy farm, Silvermere Holsteins. Photo by Pip Farquharson.

Colin Thompson on his dairy farm, Silvermere Holsteins. Photo by Pip Farquharson.

Regardless of which brand they’re buying, consumers know what they’re getting with cow’s milk. It’s made up of milkfat, protein, lactose and minerals in water and its nutritional benefits are wide-ranging. It contains host-defence proteins, is an important source of calcium for bone health in children and adolescents, and it has other advantages such as assisting with the iodine needs of pregnant women.

Colin says: “To use the word ‘milk’ for anything other than fluid from lactating animals is deliberately misleading.” He believes plant-based producers are trading on milk’s good name and reputation to the detriment of consumers and farmers alike.

Plant producers disagree. Nick Goddard, CEO of the Australian Oilseeds Federation says, “The train has left the station on this. We don’t see it as an issue. Milk has been associated with soybeans for a long time. It’s a descriptive term for the beverage made from soybeans.”

Ripe soybeans ready for harvest. Milk has been associated with soybeans for a long time. Source: Getty Images.

Ripe soybeans ready for harvest. Milk has been associated with soybeans for a long time. Source: Getty Images.

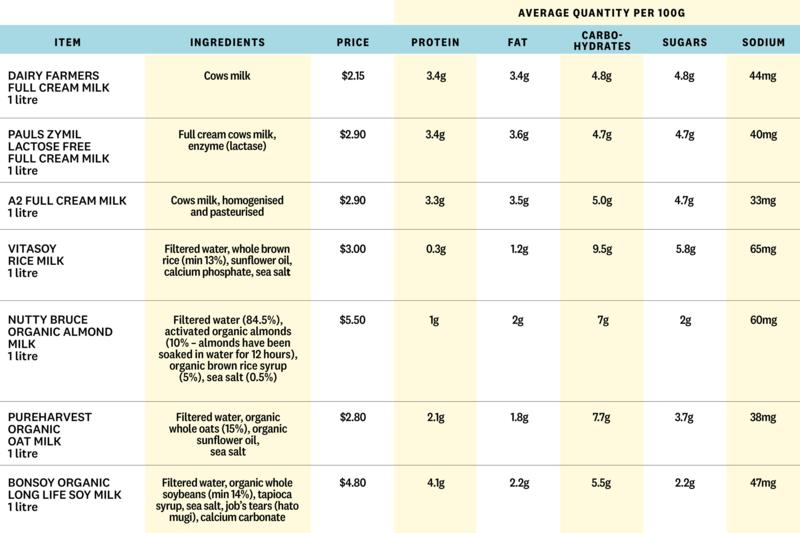

But plant-based milks do vary enormously in nutritional characteristics. Consisting largely of water, they can have very few other ingredients, and then in small amounts – almond milk products can contain as little as 2% almonds – and may match only one or a couple of the dietary benefits of cow’s milk.

Most plant-based milks consumed are retail products, often fortified with protein, flavours, sweeteners and other additives, mimicking the taste, appearance and nutritional profile of cow’s milk.

Commercially, the dairy industry knows it is time to seriously consider the repurposing of the term ‘milk’ in marketing. Ian Zandstra is a former chair of the Dairy Farmers Milk Co-operative, a dairy farmer of 36 years standing at Nowra and a member of NSW Farmers’ Dairy Committee.

RELATED ARTICLES ON DAIRY FARMING:

-

The dairy farmers innovating through education

-

Dairy farm thrives after deregulation

-

Holstein single-source dairy farm a family affair

-

Dairy farmers in danger of disappearing

In the past, Ian didn’t have an opinion on plant-based alternatives using the word milk.

“Once it didn’t seem so significant, it was only soy, but now other alternatives to ‘true milk’ are gaining market share”

“If we don’t defend our patch we’ll be the loser,” says Ian.

His stance is supported by statistics released by specialist agribusiness lender, Rabobank. Last year, it estimated that global retail sales of dairy alternatives had increased 8% annually over the last decade.

The global trend towards ‘dairy-free’ reflects not just a preference for plant-based milks, it also marks the reluctance of many consumers to drink milk. Last December, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences forecast that Australia’s milk production will fall by 4% in 2019.

Hot debate about milk labelling internationally

Australia’s food safety regulator,

Australia New Zealand Food Standards, defines milk as the mammary secretion of milking animals and imposes regulations on how milk can be labelled and made.

However in the same way peanut butter is recognised and sold as having no connection to butter, ‘milk’ can be used in connection with the sale and advertising of plant-based beverages if other words provide context – for example, the addition of ‘almond’ ahead of ‘milk’. This begs the question, Colin Thompson asks, “Why can’t it be almond juice?”

Milk is defined by ANZFS as the mammary secretion of animals- meaning ‘milk’ made by plants should not be using the term. Photo by Pip Farquharson.

In 2017 the global dairy industry was buoyed by a ruling of the European Court of Justice that soy products could not be marketed using designations such as ‘milk’ or ‘cheese’. The court was upholding European Union agricultural legislation that says the term milk can only be used to describe products from “normal mammary secretion obtained from one or more milkings”. Adding words like ‘tofu’ or ‘soya’, to make it clear they are dairy substitutes is not permitted either.

EU regulations do allow exceptions for products that have a long association with dairy names, including peanut butter, almond milk and coconut milk.

The debate has also been unfolding in the United States. The National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) has been lobbying the US government for two decades to enforce the “standard of identity” for milk and prevent beverage manufacturers using dairy terms.

In July 2018 the NMPF stated, “It’s high time that we end the blatant disregard for federal labelling standards by marketers of nutritionally inferior dairy products.” The Food and Drug Administration Commissioner is currently taking submissions as he looks to modernise standards of identity for dairy and other foods competing with plant-based substitutes.

Marketing the nutritional benefits of cows milk

Yet there is good news for dairy farmers with the emerging health-conscious market. “The dairy industry needs to be more innovative and promote milk as the world’s most nutritional drink,” Colin Thompson says.

Rabobank identifies the largest consumers of dairy alternatives as Millennials and Generation Z, due to perceptions of health and sustainability benefits, and the dairy industry has begun to respond to those concerns.

Farmers are being more conscious about marketing milk as a healthy, high-protein drink. Photo by: Nick Cubbin.

Farmers are being more conscious about marketing milk as a healthy, high-protein drink. Photo by: Nick Cubbin.

With the exception of soy milk, plant-based milks struggle to rival dairy milk for protein content, a fact that has been turned by Australian brands to their advantage. The Rokeby Farms label, for example, markets ‘whole protein’ breakfast smoothies sold in smaller sizes for a health-conscious consumer-on-the-go. The Whole Dairy labels its milk as ‘high protein’, while the selling point on the Made by Cow label is ‘cold-pressed raw milk’.

Australian consumers are now also developing a taste for fermented milk drinks linked to good gut health such as kefir and the Scandinavian-style yoghurt drink, filmjölk.

Then there is scope for the dairy industry to produce products suitable for people with medical conditions requiring a low-dairy diet. Lactose-free milk is a successful response to the changed market, with up to two-thirds of the world’s population thought to be lactose intolerant (for more on this subject, see the opposite page).

Another product, A2 milk, is produced from cows that naturally exclude the A1 protein in their milk, which is thought to aid digestion for those intolerant to lactose.

It is clear times have changed and food labelling has not kept pace but that doesn’t mean the fight is over. Says Ian Zandstra, “It’s become a commercial issue. We’re competing for the consumer.”

UPDATED VIDEO: 17 JULY, 2019

Nutritional values of cow and plant milks

Coffee craze fuels the demand for plant-based milks

When The Farmer’s sub-editor Sandy McPhie dropped into a cafe in inner city Sydney to buy her morning coffee, she was surprised to be told that dairy milk was not on the menu. “We have macadamia, almond or soy,” the barista told her.

The big city coffee craze has been fuelling much of the demand for plant-based milks. In New York, coffee drinkers expressed outrage on social media when their favoured oat milk brand sold out, and in the UK, a major coffee chain reported that one in 10 hot drinks were now ordered with dairy alternatives.

It’s a similar story in rural NSW. Juliet Robb, who opened her landmark cafe the Long Track Pantry at Jugiong in the Riverina in 2006, says: “It wasn’t long before we started adding soy milk to our offering. But we have thus far resisted introducing almond milk, and for that, I feel like we’re not that popular.”

Juliet Robb, owner of The Long Track Pantry in Jugiong. Source: supplied.

Juliet Robb, owner of The Long Track Pantry in Jugiong. Source: supplied.

‘Barista-style’ milk alternatives often have added stabilisers to avoid the product from splitting when added to hot drinks. Despite this, many coffee drinkers see plant-based milks as an entry-level way forward to a healthier and more sustainable way of living.

Research reveals that dairy alternatives are largely used on breakfast cereals and in drinks like coffee and smoothies – and that 90% of plant-based milk consumers still buy other dairy products, including cheese.

Juliet Robb’s children are lactose intolerant, but she doesn’t give them plant-based milks. “I didn’t want them to drink soy because I know how processed it is,” she says. “So at home we drink A2 milk.”

Juliet has noticed another trend – that more of her customers are avoiding dairy milk but are not replacing it with anything else. She estimates her customers drink up to five coffees per day, which can add up to a significant amount of milk. “A lot of people find a cup of milk hard to digest,” she says

“About one in five drink milk-less coffee.”

She estimates her customers drink up to five coffees per day, which can add up to a significant amount of milk. “A lot of people find a cup of milk hard to digest,” she says.