THIRD-GENERATION farmer Stuart Larsson was greeted with puzzled looks and the occasional “hippie” reference when he ventured into organic farming more than 20 years ago.

Today, he and wife Katina are the proud creators of

Mara Seeds, a diverse 3,240-hectare family enterprise that produces certified organic soybeans, livestock feed, fertilisers, pasture seed and beef at Mallanganee, near Casino on the NSW North Coast.

Stuart is now regarded as a pioneer in the NSW organic industry and the modest Larsson farm that started in 1914 now supports the careers of daughters Holly and Louise, and its products are the backbone for businesses operated by son Ross and nephew Paul.

“We replaced the dairy herd with beef cattle in the early 1970s, but the cattle market crash in 1974 forced us to look at other options, and soybeans was the first choice,” Stuart says.

Soybeans were a new crop for the region and proved to be a worthy first choice, he explains. But rising input costs and flat yields eventually led to an investigation into new farming methods.

Inspired by a working holiday on Amish farms in the United States and follow-up discussions with scientists, Stuart’s organic path started with using compost to improve soil biology and structure.

“I learned over time that if you look after the soil it will look after you,” he says. “This is a key principle for organic farming, as it is for good conventional farming systems.

“A good conventional farmer would make a very good organic farmer, as they know the importance of looking after the soil.”

Cropping still headlines the farm’s gross returns, with significant premiums for organic soybeans. Grain from organic wheat and maize crops are key ingredients for livestock feed products, which are used to supplement the beef grazing enterprise and sold to organic beef, dairy, and poultry producers across Australia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Reaping the rewards of biodynamic farming

Improving pasture growth with carbon grazing

Family run sustainable paddock-to-plate business tastes good

Nothing is wasted in this fully integrated farm business. Waste from the organic soybean crop, which supplies 85% of Vitasoy’s organic beans, is incorporated into livestock protein meals, and dry licks and residues from wheat and maize crops are the base ingredients for compost-based fertilisers.

Stuart, Katina and Louise with the organic Katambora Rhodes grass seed, which they supply to organic beef cattle operations and to the pasture seed market.

Stuart, Katina and Louise with the organic Katambora Rhodes grass seed, which they supply to organic beef cattle operations and to the pasture seed market.

“When we first went into organics more than 20 years ago there was virtually no inputs available,” Stuart says. “There were no stock feeds, no fertilisers and no-one wanted to know about it.

“So we had to develop those ourselves over time and that long process has now become what we call SOFT Agriculture, which stands for Sustainable Organic Farming Techniques. This is the farm’s marketing arm for the livestock feed and fertiliser products.”

RELATED: Henty farmers committed to regenerative agricultural practices

Rock phosphate from a mine in Monto, Queensland, organic trace elements and biochar, a carbon-rich charcoal product, are added to the livestock feed and fertiliser ranges. An onsite animal nutritionist and an agronomist tailor the livestock meals and dry licks to suit the breed and farm soil type.

“We can’t keep up with demand for organic livestock feed in the domestic market, particularly in the last couple of years.”

Stuart also calls himself a carbon farmer and is impressed with the recent addition of biochar to the farming system. “I am excited about biochar and it’s really starting to take off.

Farmers use biochar to maintain sustainable soils

“Farmers who are using it are reporting up to 10% productivity gains, the manure is better quality and it helps lock up methane and ammonia.

Normally, you have to gradually introduce the high-protein pellets to the weaners, but with the biochar included they can take to it straight away without any acidosis.”

Pasture seed production and an 850-cow beef herd complete the Larssons’ range of organic commodities. Two varieties of Rhodes grass and two of Setaria are harvested for seed, which is sold to organic beef producers and on the conventional pasture seed market.

The Hereford and Angus-cross herd are rotationally grazed and supplemented with a dry lick, which provides a protein source all year round.

The calves are also treated to the homemade high-protein weaner pellets from about six months of age. They are grown out to about 300kg liveweight, processed at the

Northern Co-operative Meat Company in Casino – and Mara Organic Beef then finds a home in supermarkets in Asia, mostly Singapore.

RELATED: From paddock to Asia, the brand smashing the supply chain

“The supplementary feeding enables us process on average 40 head every three weeks, even in tough times,” says Stuart. “Maintaining a consistent supply to our customers is vital.”

Stuart says returns for organic beef are generally 30% higher than for conventional beef in the export market, and they have not been subject to recent market fluctuations.

The grain silos on the Larsson family’s farm. Grain crops are key for the livestock feed that they sell to organic producers across Australia.

The grain silos on the Larsson family’s farm. Grain crops are key for the livestock feed that they sell to organic producers across Australia.

“Our prices for the organic beef have not changed for a few years. Returns for conventional beef producers have increased in recent years, which is a good thing for the whole industry.

“I have always had the view of don’t get into something unless there is a market. In the case of organic farming, initial costs of production are high until you get your system and soils working, but there is clearly market demand.

“The agricultural industry has been used to other people marketing their products. That’s not the case anymore. Consumer demand for local products has stepped in and changed that.”

Stuart’s next farming adventure is industrial hemp and he is in the process of trialling varieties to improve yields and pest resistance.

Swell in farm fresh organics creates challenges and opportunities during the Australian drought

Where the Larsson family have been pioneers, many others have now followed. The Australian organic industry has numbers most businesses can only dream of – and new research suggests its health is only going to improve.

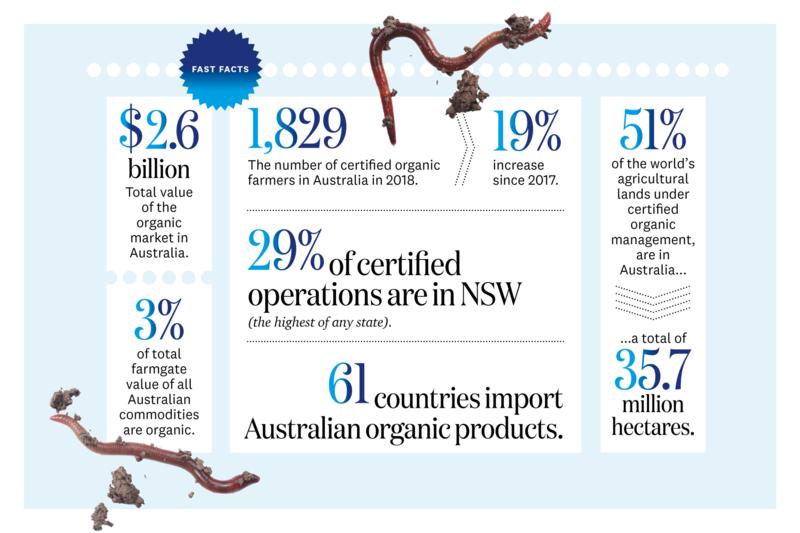

The research, conducted by the University of New England and the Modium Group, now values the industry at $2.6 billion, with a compound annual growth rate of 13% since 2012.

The Australian Organic Market Report 2019 notes that fruit, vegetables, nuts, meat, grains, eggs and poultry meat dominate the organic food range, with a 17% growth in fruit, vegetable, and nut production since 2017.

Organic farmers Quentin and Lesley Bland are innovating with organic broccoli powders.

Organic farmers Quentin and Lesley Bland are innovating with organic broccoli powders.

The industry has not been immune to drought however, with a slowdown in the growth of organic meat, dairy, grain, wine, eggs and livestock feed production. On the processing side, the number of certified operations has jumped to 2,077 – a 45% increase on 2017. Processor numbers have grown by a whopping 523% since 2002.

CEO of

Australian Organic, Niki Ford, predicts the growth will continue as the industry reacts to significant global developments.

“International trends tell us consumers want a greater understanding of product origins and clearer traceability. Australian consumers are certainly no different,” Niki says.

“Certified organic products offer consumers a trusted experience as they know that purchasing a product with a certification mark that it has gone through a rigorous process to ensure they are getting what they are paying for.

“Over six in 10 shoppers say they have purchased organic fruit and vegetables at least once in the past 12 months. Fruit and vegetables are the traditional category for shoppers, but we have seen strong gains in skincare, cosmetics and non-alcoholic beverages.”

Source: Australian Organic Market Report 2019

Despite the healthy growth numbers, the organic industry is still confronted with a number of hurdles. Value and trust remain entrenched as the major barriers for shoppers who were surveyed for the Australian Organic report.

A substantial 61% of respondents suggested cost is still prohibitive, and the ability to legitimately identify that a product is organic has become a more pronounced issue in the past 12 months.

The industry is also working towards improving a fragmented representation of the organic sector. Formerly known as the Biological Farmers of Australia, or BFA, Australian Organic says it is now the industry body representing all farmers, certifiers, processors and handlers.

Niki says Australian Organic joined as a member of the

National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) this year to give the organic sector a strong voice in Canberra.

“Australian Organic’s membership of NFF will ensure our sector’s interests are drawn to the attention of our federal politicians and our needs considered in government decisions.

“A key issue for the industry currently is organic grain supplies. We expect grain production this year to be only 25% of average national yields due to the drought, so we are talking to the federal government about biosecurity protocols if organic grain needs importing.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Regenerating the land with a strong drought-proofing tool

Drought affected farmers: “We'll get through it"

While grain crops (cereals, pulses, legumes and oilseeds) only make up 4% of total organic production, Niki says the drought has created significant pressure on feed input supplies for organic beef, dairy, poultry and egg farmers.

Source: Australian Organic Market Report 2019

Source: Australian Organic Market Report 2019

NFF president Fiona Simson says the issues organic farmers face are common to many farmers. “Having Australian Organic join the NFF means we can get a more informed understanding of the challenges and opportunities before organic farmers and, as a result, be better able to advocate in the interests of all farmers.”

However, a single organic industry body is not set in concrete yet.

The Australian Organic Industry Working Group (AOIWG) was established in 2017, consisting of industry leaders from across Australia collaborating on establishing a harmonised national voice. This led to

Organic Industries of Australia (OIA) being established last year as the interim peak body to represent the industry.

Interim OIA chair and NSW Farmers member Greg McNamara says OIA plans to merge with the

Organic Federation of Australia in October, narrowing the peak bodies from three to two.

“OIA and Australian Organic are still working through who should be the peak body,” Greg says. “I believe the single biggest issue for the organic sector is to have a united peak body so the industry can develop a five-year strategic plan and help organic farmers take advantage of consumer demand.”

What is organic agriculture?

- Organic farming is defined as: “A production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects.” The four principles are health, ecology, fairness and care.

- Certified organic products are those which have been produced, stored, processed, handled and marketed in accordance with precise technical specifications (standards) and certified as organic by a certification body.

- Products are grown and processed without synthetic chemicals, fertilisers or genetically modified components, with a total focus on soil health. Animals are raised without growth hormones or antibiotics on a 100% organic diet.

- Organic farms are only certified after they have been operating according to organic principles for three years, and must pass an audit and review process.

- By law, produce to be exported must be certified as organic. There is no mandatory certification requirement for organic produce sold domestically in Australia – however, many farms opt for certification to boost consumer confidence.

Sources: Australian Department of Agriculture, Australian Organic, International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements

High production costs drain organic vegetable profits

.jpg)

Brendan Murray says that transport costs and decreasing wholesale prices are making it difficult for organic farmers to continue to be profitable. Photography by Brett Naseby.

High labour and transport costs and decreasing wholesale prices are hindering growth for organic vegetable grower and NSW Farmers Horticulture Committee member Brendan Murray.

Like most organic farms in NSW, the Murray family’s Nature’s Haven vegetable venture started out small. Brendan’s parents, Don and Elaine, purchased 25ha near Coleambally in the Riverina in 1999 and began converting it to organic status.

That 25ha block is now a 150ha aggregation run by Brendan and wife Ivy, while his parents operate farms in Far North Queensland. More than 1,000 tonnes of organic zucchinis, pumpkins, sweet corn, onions, sweet potatoes and snow peas are harvested annually using a workforce of up to 40 people.

Brendan says sweet corn has been the only bright spot in an otherwise dull wholesale organic vegetable market this year. “Pumpkins have been a challenge this year. Organic prices have been around $1-$1.20/kg, which is the same as conventional and below the cost of production in Queensland.

“Transport is also an issue for heavy produce like pumpkins. It’s more efficient to supply a semi load instead of just a pallet or two of organic pumpkins as a single pallet space costs $450 to transport from north Queensland to Melbourne, so we have been selling them as conventional pumpkins,” Brendan says.

With price being a major barrier for shoppers, he says some retailers are looking to drive down wholesale rates. “It’s clear that consumers want organic vegetables. That is what has driven the growth in our farming business. But they want it at a cheaper price these days, which does not reflect the high labour costs.”

RELATED: "Out of the box" farming approach creates brand value

On the plus side, a direct supply deal with Coles for their Nature’s Haven brand features a premium price and is a regular source of farm income. Having farms at almost either end of the country provides a key advantage in consistent supply.

To cover the extra labour, packing and transport costs Brendan says prices for their Queensland crops need to be almost double conventional wholesale prices, and 30-40% more for the Coleambally crops.

“I am a proud organic farmer, but with current wholesale prices, hassles with labour and the impact of drought, it will be difficult to continue growing our business.”

Organic dairy farm proves successful for Wauchope farmer

_preview.jpg) Wauchope dairy farmer Chris Eggert started producing organic dairy following the deregulation of the dairy industry. Source: Supplied by Norco.

Wauchope dairy farmer Chris Eggert started producing organic dairy following the deregulation of the dairy industry. Source: Supplied by Norco.

Deregulation of the dairy industry in 2000 inspired Chris Eggert to convert a fourth-generation dairy farm at Wauchope on the North Coast to organic production.

Four other dairy farmers joined the Eggert family in going organic at the time, but Chris and wife Ann are the sole survivors, and their 200-strong herd are one of only two in NSW supplying Norco’s organic milk range.

Chris admits the initial costs in the conversion process were high, but organic dairy farming has proven profitable.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The dairy farmers innovating through education

Dairy farm thrives after deregulation

Holstein single-source dairy farm a family affair

“It does take three years to gain organic certification and during that time you are paid conventional prices and we did invest in some composting machinery,” Chris says.

“It has been worth it though and not just in terms of economics, we really enjoy it and I would not farm any other way.”

Organic milk has joined the fresh milk range in Coles and Woolworths and is more than double the price of home-brand milks, retailing for up to $3.40 per litre. Norco chair Greg McNamara says the farmgate price paid per litre of organic milk can be up to 30c per litre higher than regular milk.

“There is reward when you get there, but you’ve got to get there first and that is the challenge,” Greg says. “Norco did a strategic plan on organic milk last year and it certainly showed that investing in the organic industry is worth it. The consumer demand is there, we just have to try to match it.”

The Eggerts diversified into organic pasture-ranged egg production in 2010, which Chris says has not proven to be as profitable due to labour costs. “Incorporating the chickens has been good for our farming system though. We rotate them around the paddocks behind the cows, which is great for the soil. Soil is king in organic farming systems.”

What do the supermarkets say?

The organics section in a Woolworths supermarket boasts its 100% Australian-grown credentials. Source: Woolworths Online.

The organics section in a Woolworths supermarket boasts its 100% Australian-grown credentials. Source: Woolworths Online.

Supermarkets continue to be the dominant source for organic food consumers, according to the Australian Organic Market Report 2019. Paul Turner, head of produce at Woolworths, says there is no doubt an increasing number of consumers are choosing to purchase locally sourced and organic products.

“In organic produce, we’ve seen double digit year-on-year growth for the past five years,” he says. “Organics is a key strategic category for Woolworths and our $30 million Organic Growth Fund is a strong testament to that.”

Woolworths recently closed the second round of its Organic Growth Fund, which is offering up to $30 million over the next five years in interest-free loans and grants, on top of contracted purchase volumes.

“Funding provided by this fund can be used by the recipient to invest in organic farming research and development and any capital expenditure necessary to commence organic farming operations or expand existing organic farming operations,” Paul says.

“Organic produce in Australia still has plenty of room to grow judging by sales in comparable countries and growers are working hard to keep up with demand.”

A spokesperson from Coles tells The Farmer that there is a growing and passionate community of customers choosing to buy organic. “One hundred per cent of Coles’ organic fruit and vegetables are Australian grown and we do work with Aussie farmers to deliver quality, availability and value to our customers,” the spokesperson says.

“Because organic farming is often at a far smaller scale and requires different farming techniques to that of traditional farming, the retail cost of organic fruit and vegetables can sometimes be higher to ensure farmers are fairly paid for their produce.”