MENINDEE hit national headlines with a series of fish kills in the Darling River, the locals’ lifeblood. The Farmer magazine headed out west in mid-May to discover a community determined to thrive, despite the odds. Deputy editor Samantha Noon discovers life in the far west is so much more complicated and challenging than a city headline can ever explain.

This isn’t the Smiths’ first rodeo. “Drought is part of life out here,” Terry Smith says.

Terry is chair of NSW Farmers’ Menindee branch, so knows a lot about the frustrations the locals all share. Along with wife Jane and two children, they live on Scarsdale Station between Broken Hill and Menindee in Western NSW, where one may question which time zone they fall under, NSW or South Australia?

It’s just before 8am, Eastern Standard Time (for the record) and a crisp morning breeze sweeps through as we wait at the turn-off for the bus to school. There Terry waves goodbye to his ten-year-old son, George, who has a two-hour round trip to Broken Hill each day. Such isolation may seem taxing, but it’s one of the reasons they love the bush.

“It’s freedom many people only dream of,” says Jane.

Vast sandy plains of red and orange paint the backdrop of their 12km driveway lined with saltbush and bluebush, with a fresh green tinge on the horizon.

They’ve been feeding and slowly de-stocking since July 2017, with only 30% carrying capacity now. The Smith family normally runs 7,000 Merino ewes and a few hundred Hereford/Angus-cross heifers across three properties, spanning 125,000 hectares in total, roughly 70-80km apart in a straight line. Properties include Harcourt Station and Waterbag Station – where Terry’s brother Wayne runs 6,000 Dorper ewes.

Scarsdale Station has de-stocked all cattle, apart from nine heifers that couldn’t fit on the last truck.

Scarsdale Station has de-stocked all cattle, apart from nine heifers that couldn’t fit on the last truck.

“There was pretty much nothing on the ground six-to-eight weeks ago,” Terry says, “until we received three falls of steady rain [since early April], 20-25mm at a time that’s nearly filled all our dams and given our stock a bit of room to move.

“With the right rain at the right time, you can go from bare dirt to good feed in seven to 10 days out here. It’s amazing what it does with the rain – as they say, just add water.”

As we drive to the house, it’s sheer luck that we spot the last mob of cattle. Terry says there are only nine heifers in the 3,650ha paddock. “These just couldn’t fit on the last truck,” he laughs.

Along with the handful of heifers left behind, they have a few pet goats, including Smokey who runs with the cattle. “The kids have a habit of collecting pets,” says Terry.

Candy the pet goat in the yards.

Candy the pet goat in the yards.

They still run 1,200 sheep in a few mobs. Their annual rainfall is usually about 230mm and the green reprieve at Scarsdale is well overdue. It’s certainly helped curb their feed bill, which reached over $1 million by early May for the past 20 months.

“We started off feeding with a mix of vetch [costing up to $360/tonne from Victoria] and wheat hay [$200/tonne from South Australia] but as prices rose we switched to grains,” Terry says. He calls it a “muesli mix with a bit of everything in it” – including sheep pellets and cracked chickpeas from Esperance in Western Australia, cotton seed, wheat, barley and corn. It’s all prepared in a mixer trailer and divvied out into sheep feeders.

An increase in vetch and wheat hay prices led Terry to make a ‘muesli mix’ for his sheep.

“I’m confident we’re going to get through winter with what [grass cover] we’ve got, which is a bit of a relief. If we can not feed for a few months – it will be a hell of a relief!”

Their abundant supply of bluebush and saltbush has been a lifesaver, too. It’s keeping their sheep going and has allowed for less supplementing in comparison to their other blocks, which have more mulga than bush.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The voices of Menindee: Far west water crisis

Going for growth with goats

Planning ahead for drought, pays off

Just like their far horizons, Terry and Jane have been planning for the long game. There’s no denying drought has been crippling but the silver lining, Terry says, is that prices have continued to go strong.

“Property prices have tripled recently [in Western NSW], everything you touch at the moment you can make a quid out of. Sheep prices and goat prices have gone through the roof, they were $8.60 and now they’re over $9/kg, that’s a record.”

It’s not quite as desperate now, the recent rain has left paddock water lying around. Terry is dreaming of the day when the big rain comes.

“When the [Yancowinna] Creek comes down in a big way it nearly takes the paddock with it, it grows feed like you wouldn’t believe. When it floods we’ll lose 15,000 acres [6,000ha] to flood out, which is five or six inches deep. This averages every two or three years. It’s normally a dry channel.”

The 24,800ha Scarsdale has 11-to-12 paddock dams. Terry has de-silted some, ready for the rain, with the loader he bought in 2014. And he’s dug some fresh ones. Almost all are full now.

Horse Lake on the property hasn’t been full since 2011, but becomes an oasis during the better seasons.

Horse Lake on the property hasn’t been full since 2011, but becomes an oasis during the better seasons.

In 2014, he cleaned out 15,000-22,000 cubic metres of silt from Horse Lake, a previously unknown railway siding 16km inside their boundary. It operated from the early 1900s until the 1970s, carting water tanks 14 times per day to the Broken Hill zinc mine. In its heyday, 1.5 million gallons a day were piped from Menindee Lakes to Horse Lake.

Today the older gum trees are struggling and the banks bear thirsty tree roots, some nearing 100 years old, Terry says. The lake hasn’t been full since 2011 but in a good season, it comes alive and the family regularly visits. “It’s a really amazing spot when the creek is full, it turns into a wetland here with thousands of birds, swans and ducks – it just doesn’t happen often enough. It’s a great spot for yabbying, picnicking and filling in a bit of time – it’s our own little piece of paradise.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Drought stories of success, not charity

Drought preparednessBranching out in dry times

Not long after purchasing the property in 2000, Jane and Terry gave the woolshed a facelift. Cementing the shed yards, fixing up the quarters and filling in old hazards made life easier for the contract shearing team of five, who visit one week each year in September and do a fine job.

Olive trees provide a handy windbreak in the sheep yards and small crop.

Olive trees provide a handy windbreak in the sheep yards and small crop.

The olive orchard, a handsome addition to the sheep yards in 2004, has cost very little for what it offers – the low-maintenance, drought-hardy crop offers a windbreak, reduces dust and provides shade for those working outside, along with a little side hustle that’s a bonus for Jane’s cooking. “Our first harvest in 2009 yielded three-quarters of a tonne, and just recently we harvested two tonne, which we sell to a co-operative in Broken Hill,” says Terry.

“Without the effects of the drought, we fetch a couple of grand for a wool bale, and yield 70% [of fleece]. In a good year it’s between 19-23 microns and less than 1% vegetable matter in the fleece lines.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Farm safety made a priority

Why is there a shortage of shearers Western NSW, a fine fit for growing wool

“It’s pretty good wool-growing country, which is why we’ve stuck with the wool sheep as opposed to switching to a shedding breed. Dohnes are good but don’t grow wool anywhere near as much as a Merino.”

The Smith family have 1,200 sheep left since de-stocking but normally run 7,000 Merino ewes in a good season.

It’s some of the best country you can get, Terry says. “We don’t have to add any trace elements in the soil, it’s warm enough so we never have a worm issue. As far as sheep go, it’s really only an off-the-board lice treatment and maybe one fly treatment so it’s pretty chemical free, but not completely, especially as we’re running Merinos.”

From afar, the pressure seems to have eased off a little. Before the rain, they’d relied purely on the Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline along with nine other farms, for both stock and domestic water. Terry says, “In a dry year we’d use 25 megalitres and since our dams filled we’re back to 30-40% now.

“Every farm on that pipeline draws water from it. In peak times when we’ve got feed but don’t have tank rain, there could be 60,000 sheep and five or six thousand cattle watering off that every day,” Terry says.

“At some stage they’re going to decommission that line – the rumour is they’re going to replace it with a smaller diameter line, as it’s no longer supplying Broken Hill.” - Terry Smith

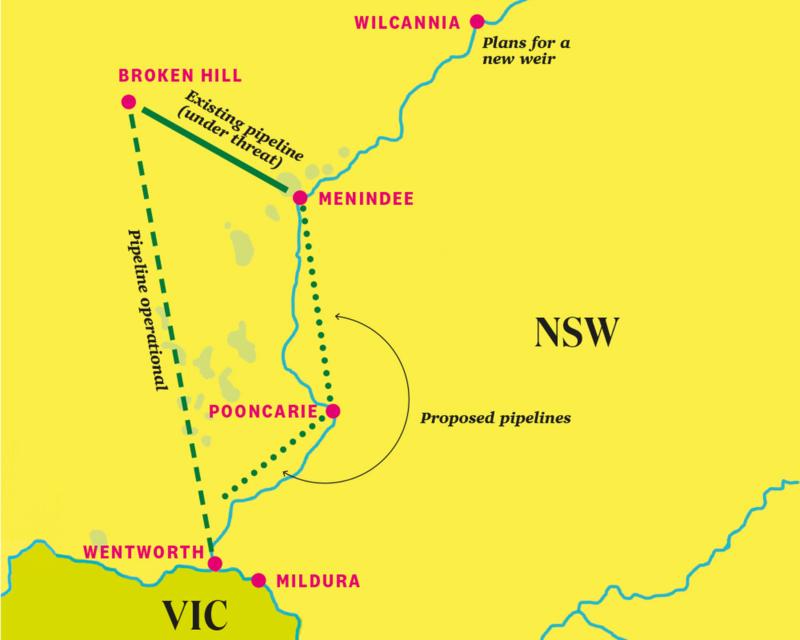

In mid-2016, when Broken Hill’s drinking water was running short, the $500 million pipeline from the Murray River at Wentworth to Broken Hill was announced and now supplies the town with up to 37.4 megalitres of raw water per day.

However the swift project completed earlier this year has left pastoralists, like Jane and Terry, wondering what the future holds. They draw metered water from the old pipeline, that comes from Lake Copi Hollow. Small communities worry that they’ve been forgotten in the feasibility study.

The Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline provides landholders with water when needed, but is set to be decommissioned. It is marked “existing pipeline” on the map, which also shows proposed pipelines and the new Wentworth-Broken Hill pipeline.

The Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline provides landholders with water when needed, but is set to be decommissioned. It is marked “existing pipeline” on the map, which also shows proposed pipelines and the new Wentworth-Broken Hill pipeline.

Details have not yet been confirmed, but locals believe the replacement pipe will link up with new proposed lines from Wentworth between Menindee and Pooncarie and a new weir planned for Wilcannia.

It coincides with the Menindee Lakes Water Saving Project proposal to reset the lakes’ drought reserve from 240 gigalitres to 80 gigalitres, a mere drop to its 1,730-gigalitres capacity.

“This has been going on for the best part of three years now since they announced the new line [Wentworth-Broken Hill] but we haven’t seen any action to replace our pipeline yet,” Terry says.

Terry points out Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline from the air as he takes The Farmer’s Sam Noon on a tour in his plane. Photo: Samantha Noon

“Up until this rain a few weeks ago, it’s just been another thing playing on your mind all the time when you’re out feeding, wondering if for some reason someone in Sydney is going to turn the water off. Essential Water to their credit have guaranteed they’re going to keep our water up.”

There’s no underground water at Scarsdale – or if it’s there, it could be 120m deep, says Terry. So without pipeline water, life is impossible. “We can’t seriously be expected to cart water, as was suggested by some of the government departments, for 5-6,000 sheep every day – I’ve got better things to do with my time.”

Video produced by Samantha Noon on her mobile phone.

Waterbag Station has sufficient bore water and Harcourt used to draw stock water from the Darling River. But Terry says: “The Darling River south of Menindee has become unreliable due to water management. Water in this area has been a huge problem for 20 years at least."

SPECIAL FEATURE > The voices of Menindee: Far west water crisis

"It’s really only hit the headlines with the fish kills in Menindee before Christmas. It’s just been a burning issue here for a long time. We’ve been banging on to the government to change what they’re doing otherwise they’re going to bugger the lakes.”

Kangaroos and wild dogs, a growing challenge in Western NSW

With the gentle reprieve of rain and green pick shooting up, their greatest challenge awaits – kangaroos and wild dogs. “Kangaroos have fast-forwarded this drought by six months at least,” Terry says.

“A recent count was 17.3 million roos on the Western Plains, that’s three kangaroos for every sheep.”

Kangaroos have become a huge challenge in Western NSW. Terry says they’ve fast-forwarded the drought by six months.

Terry has shot two dogs in the last four years and his neighbours got five. “There’s a lot of pressure coming from up north. In South Australia, landholders were shooting up to 80 on a water run. When we moved here in 2000, we’d never heard of a dog, now everyone’s got tracks, seen dogs or shot dogs. It’s becoming an issue. We’ll end up like Queensland. It’s a matter of how much energy and effort we can put into it.”

At the NSW Farmers Goat Conference in Broken Hill in March, Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA) put forward policies on pests. “There’s a bit of pressure going on from producers onto MLA. Australian Wool Innovation [AWI] has been really good with their workshops and their aerial baiting campaigns. But wool growers are a bit sick of other stock breeds reaping the benefits [of dog control].”

They would like to see MLA help out, he says. “Rangeland goats are such a big industry and so widespread. Dogs can take goats and it’s largely unnoticed. Our major concern, with such little water, is the native wildlife that are being supported.

“While that water [from the Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline] was reasonably priced, we’re still paying a fair bit to water kangaroos and birds. They’re not really ours and we don’t mind, but it’s a bit frustrating.”

RELATED PEST ARTICLES:

Fair game on feral deer

Kangaroos: pest or marketing opportunity?Bird's eye view of outback life

Terry got his pilot’s licence in 2013, and a light sports aircraft and hangar in 2014, so he invites The Farmer to see the problem from the air.

To the west, a few kilometres away, a shiny road train preps to unload towers of hay, billowing dust behind it. Not far ahead, we see a train, with over 30 carriages, heading for Menindee.

There’s brown as far as the eye can see, but pockets of green and masses of roos – thousands at a time. We can see channels glinting with water from the recent rain, and isolated dams full – for now.

“They say water is for fighting and whisky is for drinking,” Terry jokes, as we fly hundreds of metres in the air. It’s easy to see the joy in his face when he’s flying.

“You can rip around nice and smooth in the morning, it’s just beautiful.” He checks water and livestock of a morning as there are less thermals. “It saves days compared to mustering on the ground.”

Terry takes The Farmer’s Sam Noon for a flight over Scarsdale in his light sports aircraft.

It’s dry, life is tough and there’s always work to be done. But whether on the ground or in the air, the land is full of surprises and its sheer remoteness adds to the adventure.

Sharing their story of outback life

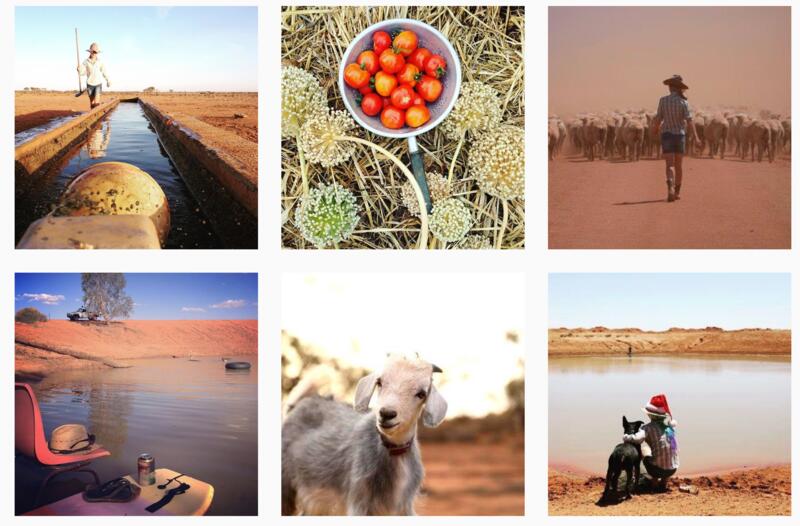

Along with all the hard yakka, both Terry and Jane find time to muster an impressive social media following. Terry’s Instagram page

@TheShadyFarmer and Jane’s blog and Instagram

@TheShadyBaker, help educate others about their life on the land.

Jane’s interest in photography has blossomed since Terry bought her a DSLR camera in 2013. They are nearing 10,000 Instagram followers collectively.

Snapshots from Jane Smith’s Instagram account, showing everyday life at Scarsdale station, Broken Hill.

Snapshots from Jane Smith’s Instagram account, showing everyday life at Scarsdale station, Broken Hill.

Many of Jane’s posts reflect her love of growing and cooking, especially when daughter Annabelle, 12, is home from boarding school. She leads workshops and shares recipes in Graziher magazine and on her blog.

“Seeing this water makes my heart sing and also sigh with relief. It’s amazing how a little bit of moisture in the ground helps both physically and mentally.” - Jane Smith

“It has enabled us to start on a major overhaul of our garden.” She let her garden go in the last two years as the house tank supply dried up and they chose not to use the Menindee-Broken Hill pipeline water.

“It’s the same as paying water rates in town, which is fine but you don’t want to be pouring that onto your garden. The good news is, we’ve finally got water back in the house tank, so I’m looking forward to getting back into it."